The Hawaii Missile Alert Culprit: Poorly Chosen File Names

This article was originally published on Medium, on January 17, 2018.

Saturday morning, January 13, 2018 at 8:09am Hawaii time, a staff member of the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s (HIEMA) State Warning Point office was going through their routine shift change checklist. They went through the same checklist every time they started their shift. It was routine. It wasn’t interesting.

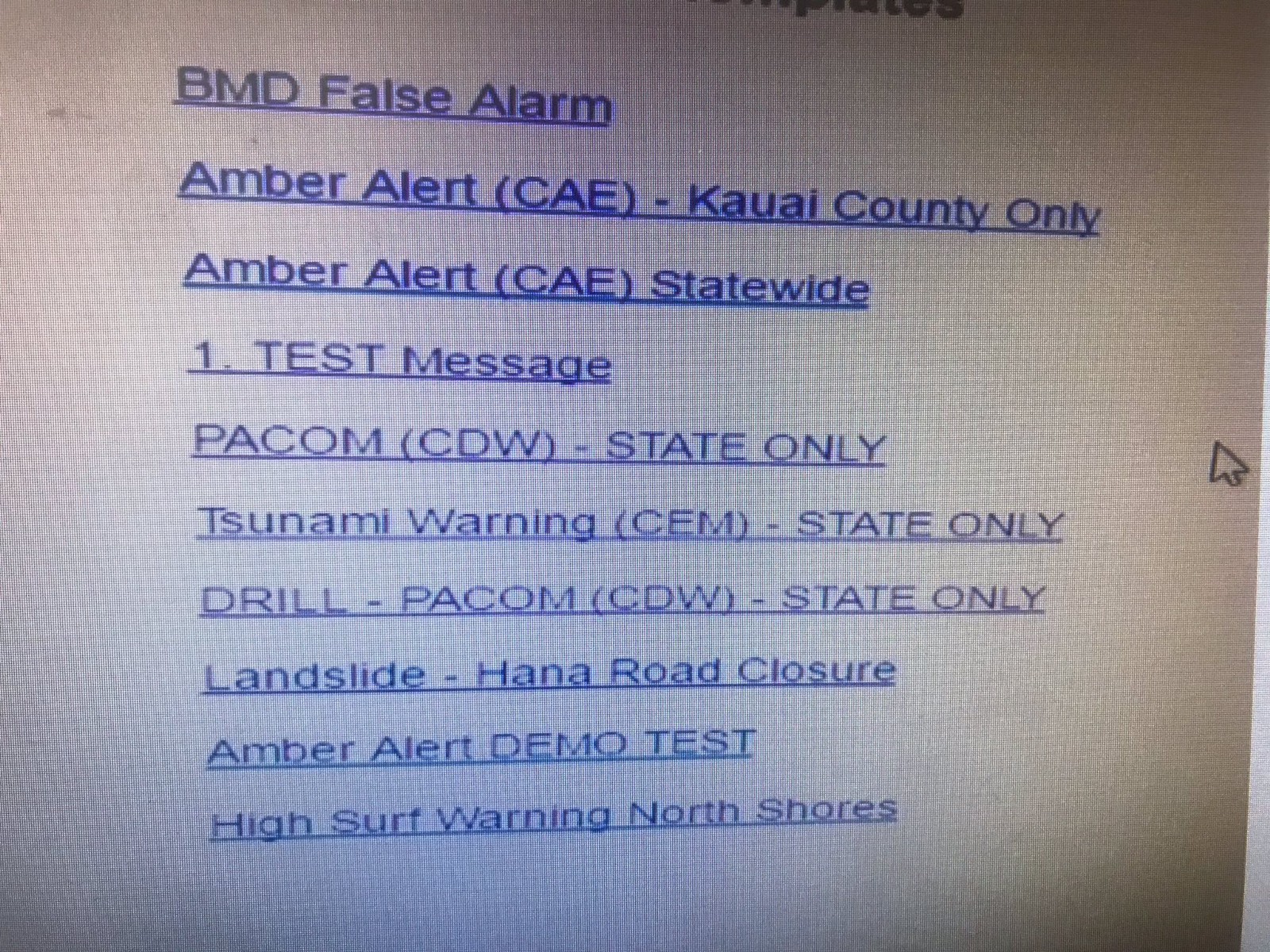

At one point, they opened up their IPAWS alert software, retrieved a list of saved “templates” and picked one from a list of 9. What they picked was named PACOM (CDW)—STATE ONLY.

Only, this wasn’t the template file they meant to open. The template they meant to open was named DRILL—PACOM (CDW)—STATE ONLY. Other than the word DRILL in the file name, the two files were nearly identical. I say nearly, because there was one other difference: The drill version sent a message only to test devices, while the non-drill version sent the exact same message to every mobile phone in Hawaii.

The message was ominous. BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.

The State Warning Point staff member didn’t immediately realize they’d chosen the wrong file. Nothing in the system would tell them they had. The clicks and confirmations were exactly the same for either file. They wouldn’t realize their mistake until a few moments later, when their personal phone buzzed with the alert, as did everyone else’s in the State Warning Point Emergency Operations Center. Oops.

Sending a message to millions of phones about an incoming ballistic missile should, one would think, have a confirmation message. It did. But so did the test message. It also required the user type in a special password to ensure they intended to send the message to every recipient, but so did the test message.

The crux of the error was choosing the wrong file, from a list that looked like this:

It’s not hard to see how the wrong file was chosen. These seem to be listed in chronological order, newest to last. (The first file BMD False Alarm was added right after the false alert went out and the Governor issued a statement. It contains the message used to tell everyone that the NOT A DRILL message in fact was a DRILL.)

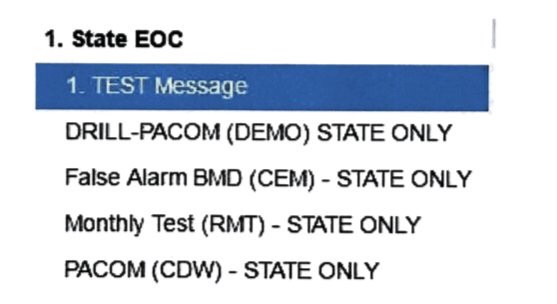

There’s an alternate template list floating around: (It seems the state isn’t sure which State Warning Point uses.)

In either case, you clearly see that the DRILL file name is almost identical to the actual file name. (CDW is Civil Defense Warning.) This list is alphabetical, which isn’t much better than date ordered.

Planning For This Mistake To Happen

This wasn’t a thoughtfully designed menu, any more than any random collection of user-named objects are. Yet, to get here, a lot of careful planning had to happen.

The system used to send out the alerts is called IPAWS—the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System—managed by the US Government’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in association with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The cellphone portion of IPAWS is known as the Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) system.

States and counties can get access to the IPAWS system to post emergency notices, from everything from road closures to AMBER alerts (child abduction alerts).

Hawaii has had their system in place for a while, which they used for weather related issues, like landslides that close roads and tsunami warnings. In November, HIEMA concerned about rising tensions with North Korea, put out a new emergency preparedness plan, which included WEA messaging in case of a ballistic missile launch.

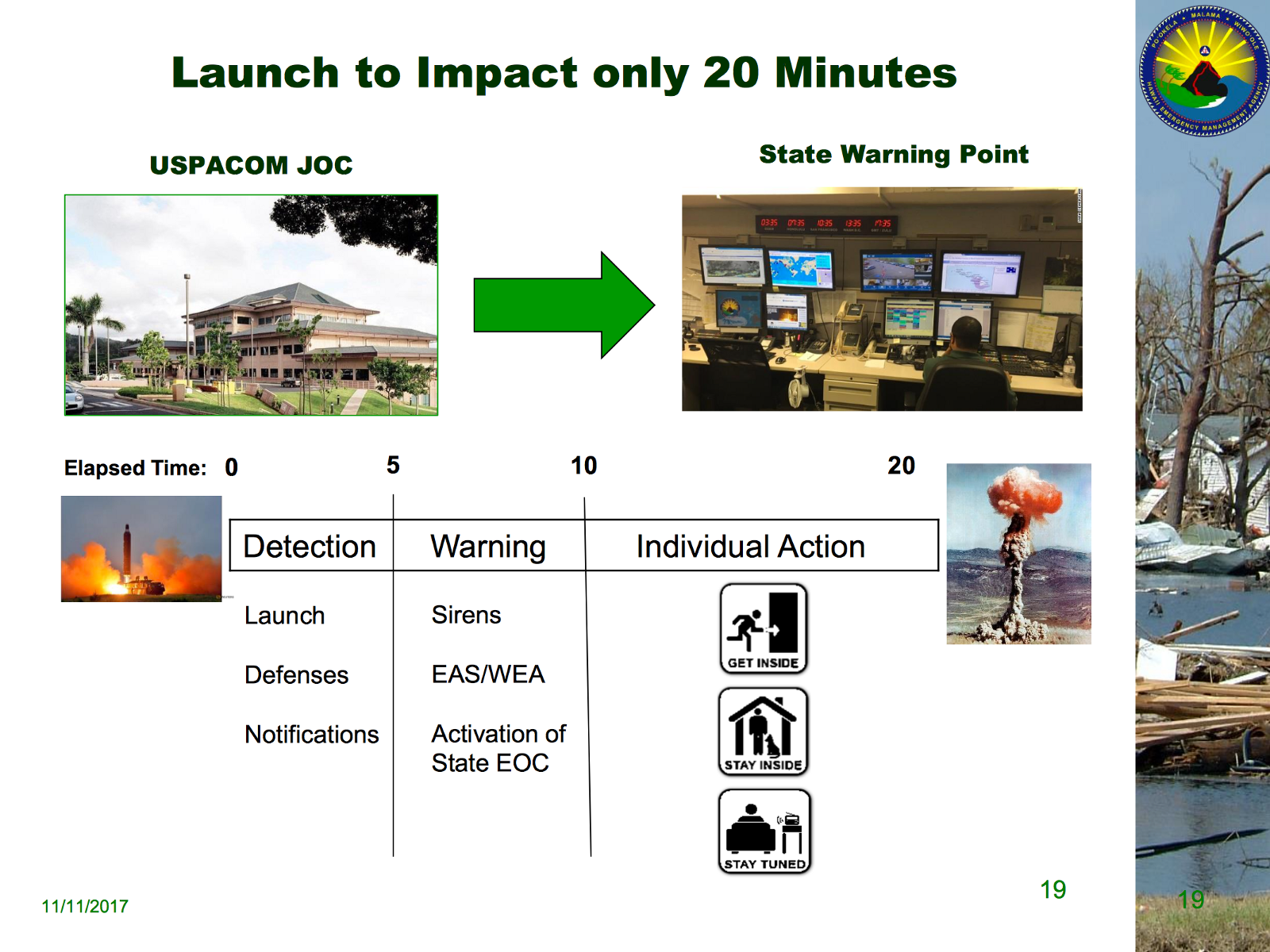

Here’s a slide from HIEMA’s emergency preparedness slide deck, stating their reaction to a missile launch.

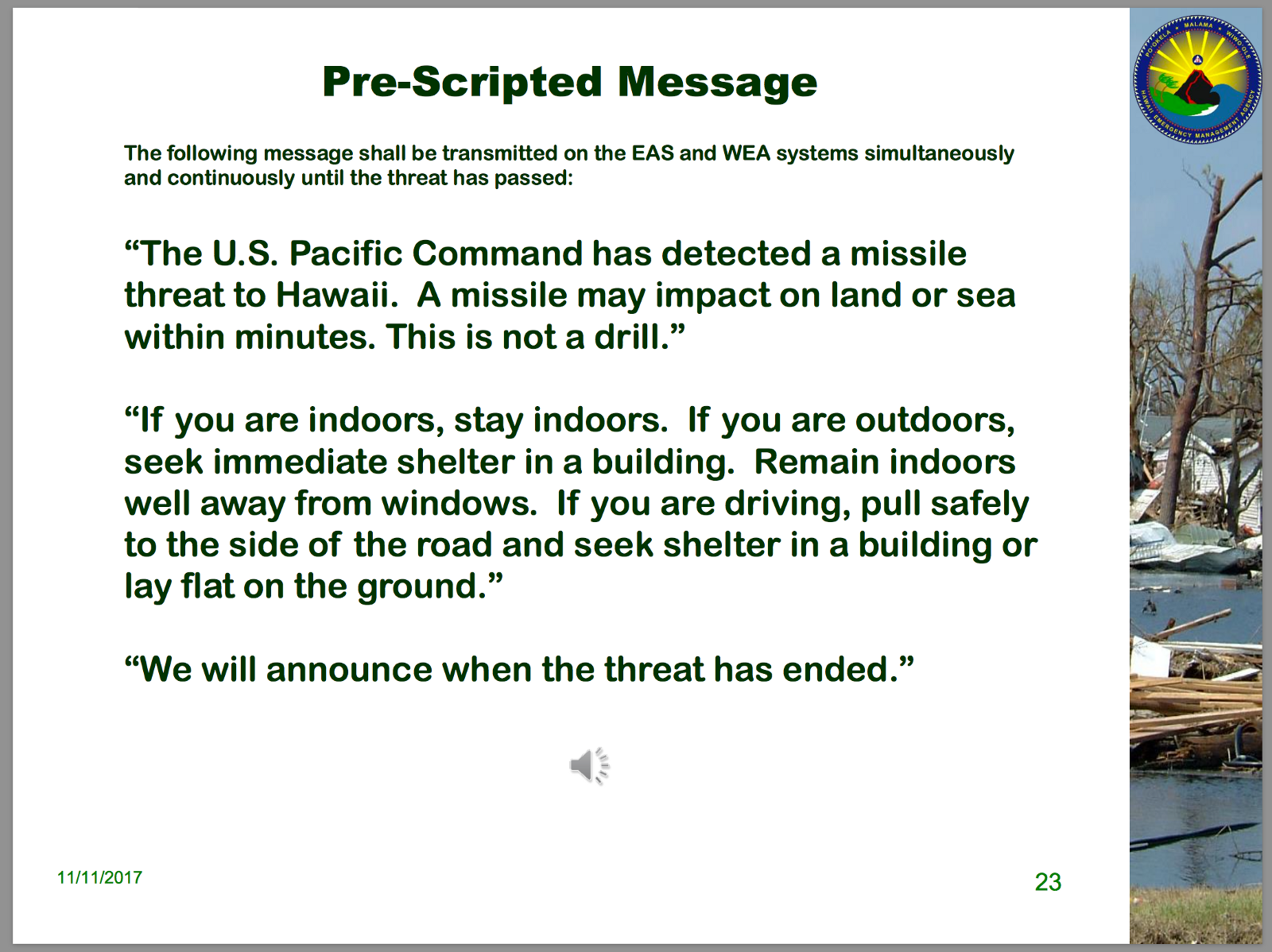

Here are the messages HEIMA recommended:

You can see the actual message that went out was very close to the messages recommended in HIEMA’s plan. (WEA has a 90-character limit, so the recommended 138-character message needed to be shortened.)

I’m guessing, with these new guidelines in place, the State Warning Point updated their saved messages, first including the drill as a regular practice, then adding the actual message. (It seems they decided to add a template for tsunami warnings at the same point, as that fall in between to the two PACOM messages. PACOM stands for the United States Pacific Command, the military joint coordination office that monitors the Pacific region.)

FEMA lists 23 approved vendors of IPAWS alert origination software. Most of these are either Software as a Service or iOS apps. (Yes, someone can alert their entire state from their phone.)

HIEMA hasn’t revealed which vendor they’re currently using. (I’ve been told FOIA requests have already been filed to learn more about the systems used in Hawaii and other states.) It’s unlikely the HIEMA implementation was customized in any way. It takes quite a bit of work to get FEMA certified. Leave that work to the vendors.

If you visit the websites for the various approved vendors, you see some nicely designed systems. Here’s one from a company called Alertsense:

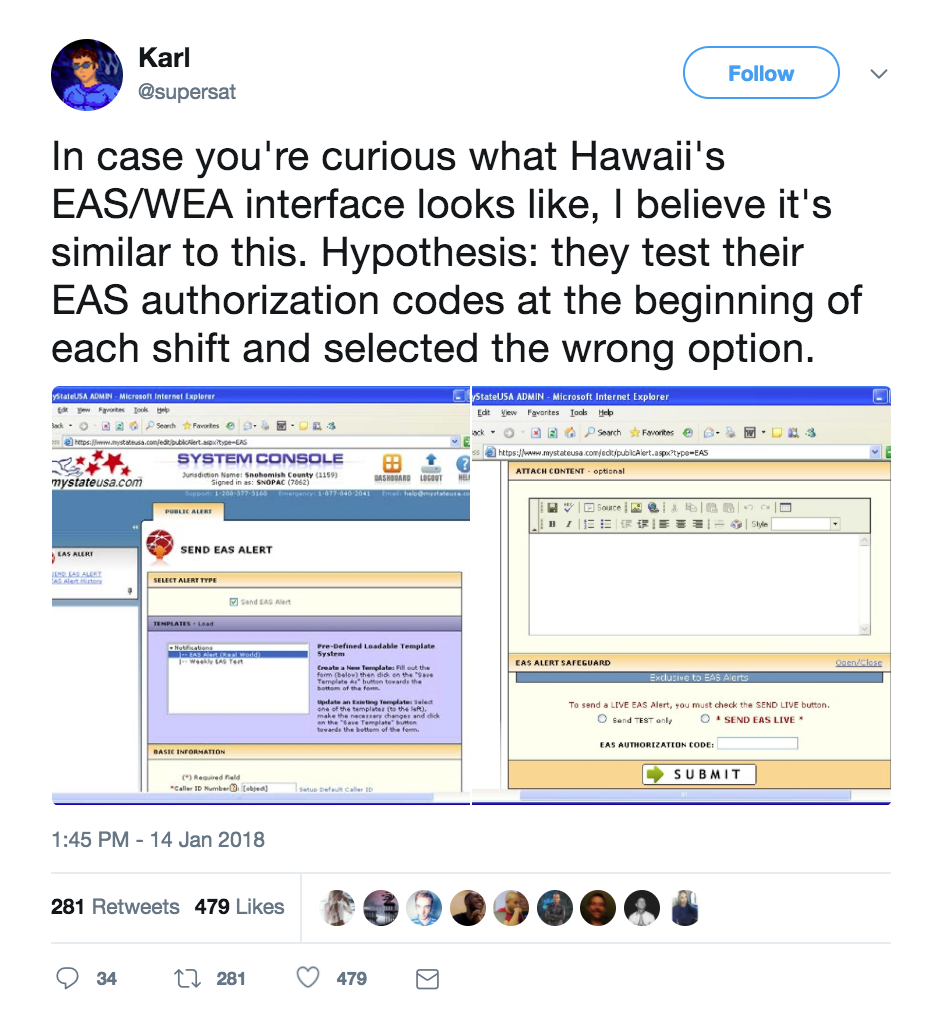

It seems to be a cleanly designed system. However, it has a predecessor and it’s possible HIEMA is using something that looks more like this:

Governments, which are often about saving their taxpayers money, don’t pay for upgrades. Especially for systems that aren’t broken. Hopefully, we’ll learn more soon about the specific system Hawaii is using.

This Mistake Has Likely Happened Before

My reaction, upon seeing the system involved, was why hasn’t this happened before? After all, choosing a wrong file is a common mistake. If the way you send an IPAWS message is to select a predefined template, then it’s likely someone picked the wrong one in the past.

However, it wouldn’t make the news. Most IPAWS alerts are for AMBER alerts and local weather issues. If the wrong message was sent out, say for a road closed by flooding, most people wouldn’t know there was an issue. If they weren’t near that particular road, they probably wouldn’t give attention to the message at all, even if it was a mistake.

IPAWS messages are usually local. A statewide message is rare. That’s what made this incident so public.

File Names Are The Culprit

Have you every known someone who loaded an old version of a file, when they meant to use the most recent, then accidentally saved the old data over the new? That is, in essence, the problem we saw here.

This is a classic user experience problem involving file name conventions. Users often do not choose file names thinking will I make a mistake in the future and choose the wrong file? We make mistakes with our files all the time, grabbing the wrong version when two files are similarly named.

If we want to ask ourselves, how would we prevent this from happening again, we have to look at how the IPAWS messages are stored for future use. The system, as it works today, relies on users to save the message templates with a meaningful name. If they fail to do so. If they choose a name that’s quite similar to another, this mistake will happen again.

There’s no system enforcing naming convention, just like there aren’t naming conventions for any other files in any other filesystem. Our systems don’t force a specific file naming regimen on the users, to ensure that every name is clear and distinct, so they’ll prevent naming confusion in the future.

A Possible Solution—Get Rid of File Names

In many ways, file names are an anachronism from days of old, when reading data was slow and space was costly. We could eliminate them in many cases, and this is one of them.

For an IPAWS WEA message, there are two distinct identifiers that we could use instead of a file name: the message itself and who it’s broadcast to. The message (BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND) is the most important thing and would distinguish it from other messages. The design could use the message as a primary indicator.

The design could also separate drills from actual emergency alerts. There could be separate lists for the drills, which are clearly distinguished by location and other distinct visual coding (like color shading).

Using the message as the identifier and separating out the drills would do a lot to prevent this problem from recurring. Frankly, this is a classic microinteractions problem. Good design could go a long way to make sure we never have this problem again.

Of course, this would be up to the vendor of the software. And there’s 23 vendors in this case. Is it FEMA’s responsibility to mandate this type of UX change? Or would the vendors do it just to avoid embarrassment?

We probably don’t want our lawmakers creating safety standards for file name methodologies. Or do we?

How Would We Have Predicted This Problem?

It’s easy now, with 20-20 hindsight, to see this problem clearly. But could we have predicted it the week before?

We don’t do enough work to stress test our own designs. We don’t ask whether people will confuse names they created themselves because those names are too similar. We don’t ask how we prevent panicking the population of an entire state, clogging up emergency 911 call centers, possibly putting anyone having a real emergency at risk.

In emergency preparedness operations, drills are a regular practice. FEMA, state emergency operations, and local first responders regularly hold drills. In these drills, they try to anticipate what might go wrong. They create scenarios that push at the extremes (what if a terrorist attack happened during earthquake recovery?), then hold retrospectives to take apart what happened and where the system didn’t hold up.

In these drills, product and service vendors are invited to participate. They observe how their products and services held up under the stress of simulated situations. Smart vendors also run their own drills and simulations, pushing their own products and services to extremes. These stress test their products, giving them a chance to make them more robust and effective.

These types of procedures are not common in digital products, except in the information security space, where regular hacking events have become common. (Last year, the Defense Digital Service invited the public to break into D.O.D. systems, offering a bounty for anyone who could succeed, to stress test their system security.)

What would a simulated missile launch have revealed about the operation of the system? Would we have encountered the exact opposite of the problem that happened on January 13? Would we see an operator using the DRILL template when they meant to use the official warning? In HIEMA’s emergency action plan, the WEA message needs to go out 5 minutes after detection because impact happens 15 minutes later. How many lives might be lost if a delay happened because it took 5 minutes to realize no warning went out?

We need more of these types of learning experiences, where vendors and operators work to stress our systems. We need to break down the barriers of organizations and work directly with the users, as they have a lot of perspective to offer us. Then we need to design something better, something safer for that population.

How to Win Stakeholders & Influence Decisions program

Our 16-Week program guides you step-by-step in selling your toughest stakeholders on the value

of UX

research and design.

Win over the hardest of the hard-to-convince stakeholders in your organization. Get teams to

adopt a

user-centered approach. Gain traction by doing your best UX work.

Join us to influence meaningful improvements in your organization’s products and services.

Learn more about our How to Win Stakeholders & Influence Decisions program today!